Solution to the problem of closed cement grinding in a tubular-conical mill (TCM)

1 Starting point

There are two ways to produce cement in BM: with open and closed grinding cycles. Suction BM with open circuits are easier to operate and maintain, as the unit contains significantly less additional equipment.

Disadvantage: The material is crushed once and passed through the BM. The finished product at the outlet is not classified by grain size, which leads to overgrinding of the cement.

To prevent overgrinding, only a closed grinding circuit is used in the basic industries of mining and energy. Despite the obvious advantages, only 4% of all mills in the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS) cement industry operate with a closed grinding circuit.

In a closed circuit, all the material from the BM enters the separator, which divides it into a finished product and a large fraction that is returned to the BM as excess sand for regrinding. The closed circuit has a number of advantages: it prevents over-grinding of cement and the associated unnecessary expenditure of energy and time, enables the grinding of high-quality cement, and increases productivity by 25%. The disadvantages are the numerous costly and cumbersome additional devices.

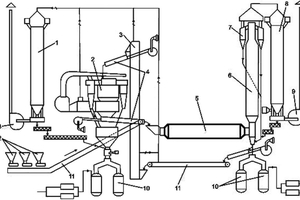

You can verify this by examining the block diagram of an aspiration ball mill in a closed grinding cycle [1], shown in Figure 1.

The total power of the large electric motors of the auxiliary equipment alone, without taking into account many small motors, is 685 kW, or 22% of the BM power.

In addition, there are other ways to achieve a closed cement grinding cycle, but all of them require the use of additional, capital- and labor-intensive auxiliary equipment, which significantly reduces the utilization of the BM‘s working time.

The only problem preventing the creation of a simple and effective technological scheme for a closed grinding cycle is the fundamental design flaws of tube BMs, which mainly consist of the chaotic, disordered movement of grinding bodies of different diameters.

The phenomenon of BMs with a rigid-variable structure (variable L/D ratio of length to diameter of the spherical mill)

It is known that tube BMs for cement with a rigid L/D ratio along their length are divided into three chambers by two intermediate chamber partitions and an outlet grid with an air lift. The complex and ineffective division of the mills into chambers was an attempt to classify the balls at least partially by size, to provide different filling rates of the grinding media and the weighted average ball, and to ensure different operating speeds of the balls along the chambers.

The filling factor and ball sorting recommended in global practice [2] (Table 1) are different in each chamber and, most importantly, their number decreases continuously by ∆ɸ = 3% in each chamber.

Thus, although not yet fully resolved, the most important priorities for optimal grinding technology have been identified for tube mills. It should be added that inter-chamber partitions are the main problem in implementing a closed grinding cycle, as they create significant resistance to the air flow that transports the end product particles out of the mill.

2 Basic examples of previous solutions

Let‘s take a look at an unusual three-chamber step tube mill from Maag, which is used to grind chromite and magnesite at the Zaporozhye refractory plant in Ukraine. The diameter of the first chamber of this mill is 2.3 m, while the second and third chambers are each 1.8 m. A step mill with a variable L/D ratio that deserves special attention.

The operation of ball mills of different designs can only be compared with each other if three initial conditions are strictly adhered to: grinding of the same material with the same mill working volumes and ball loads. For comparison, Table 2 shows the characteristic data for grinding cement of the same brand with industrial mills of different designs.

In the refractory plant, these cement mills grind chromite and magnesite, which additionally and clearly guarantees the reliability of the results achieved. The two mills compared have almost identical initial conditions. However, the working volume of the step mill is 2% and the ball filling is 10% smaller than that of the mill it is compared with, which creates clear advantages over the tube mill. The same productivity ratio of the compared mills when grinding cement and chromite-magnesite (21.9 : 12 ≈ 10 : 5.4) eliminates the randomness of the analyzed results and additionally confirms their reliability.

Despite the advantages in the initial conditions of a tube mill, the efficiency (reduced ratio of specific energy consumption per 1 ton of crushed product) of a step mill is 2.71 times higher than the efficiency of a classic mill design, and the specific energy consumption is 16.6 kWh/t, which corresponds to the best crusher designs.

This is a fundamental result that irrefutably confirms the effectiveness of mills with a variable L/D ratio, in which the following are partially implemented: classification of the grinding media, variable filling of the balls in chambers, different speed modes of the balls within the mill.

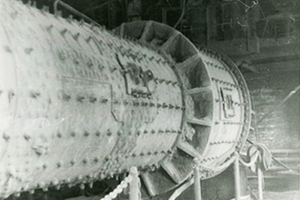

3 Universal frictionless TCM – modified structure

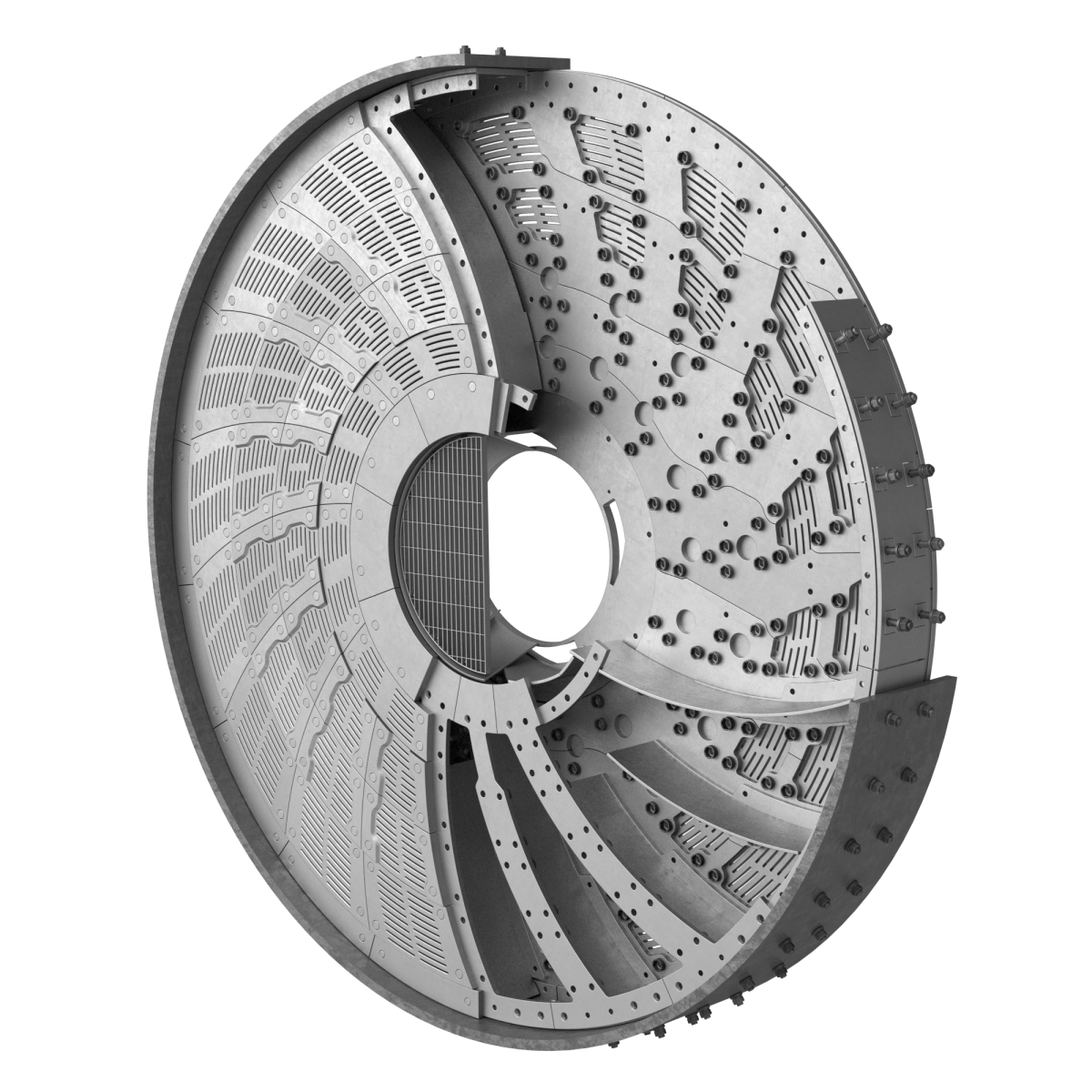

The analysis of the theory and practice of grinding, in particular of mills with adjustable speed and variable L/D ratio, made it possible to formulate the main concept of grinding [3,4,5,6] and, on this basis, to create a new generation of grinding unit: a universal tube cone mill, TCM (Figure 3) differs from the conventional BM in that it has a conical body that becomes smaller in the direction of discharge.

Basic concept of grinding: “In the TCM, the only possible and optimal arrangement of each individual working energy carrier is implemented – the grinding ball, depending on its diameter, as well as the totality of all balls in exactly corresponding cross-sections along the entire length of the cone body with the simultaneous implementation of optimal high-speed trajectories of falling balls and their turnover in each of these cross-sections.” This is the crucial point in grinding.

Directly from the solution of the basic concept of grinding follows an irrefutable series of advantages of TCM, which systematically combine the entire complex of advanced technology and design solutions into a single unit and enable the following:

1. automatically organize an ideally decreasing classification of a set of balls of different diameters in each cross-section along the entire length of the conical body, i.e., to organize the chaos of balls in the mill

2. Organize a smooth transition of optimal speed paths of falling balls and their handling depending on the change in cone radius from impact at the beginning, through crushing in the middle, to grinding at the end of the mill

3. Ensuring an optimally decreasing fill factor of the ball load over the length of the conical body;

4. Eliminating intermediate chamber partitions due to the ideal distribution of the grinding media, which increases the working volume and reduces the number of flaps on the TCM body to one third

5. Ensuring optimal self-regulation of the ball assortment (the weighted average ball)

6. Improving aerodynamics, as a single-chamber TCM is a cone nozzle (confuser) to prevent the material from “burning” in the mill

7. Creating a closed grinding circuit with a flow separator similar to a drum ball mill for coal and eliminating the outlet grid by means of an airlift, thereby radically simplifying the entire technological scheme of cement grinding

8. Achieving an optimal compromise between the advantages and disadvantages of mills with large and small diameters (L/D ratio)

9. Eliminating the need for labor-intensive grinding operations

10. Ensuring automatic, timely reloading of a ball with maximum diameter over the entire length of the single-chamber TCM during continuous operation of the mill

11. Operation of the TCM without loss of productivity with worn and smooth linings, as the speed modes are strictly dependent on the variable radius of the mill, i.e., the operation of the TCM is not critical with regard to the profile of the lining

12. Compensation for irregular abrasion of the grinding media over the entire length of the mill. Reduction of ball wear through rational filling and optimal operation

13. Increase in the machine‘s working time utilization

14. Simplification and improvement of the efficiency of the injection system for water or surface-active substances at any depth of the single-chamber TCM

15. Reduction of power consumption, dimensions, metal material consumption, capital costs, and the scope of repair and maintenance work

The above-mentioned advantages of the TCM are fully in line with modern ideas about the grinding process. It can be argued that the design of a step mill with a rigidly variable L/D ratio represents a special solution for the generalized integral multi-stage TCM design with a continuously variable structure. Increasing the number of steps in the “Maag” mill will increase its efficiency to over 271%. The integration of an infinite number of steps into a mill results in a TCM design.

The new classification mechanism for ball loading in the TCM begins at the moment the ball detaches and flies freely along the trajectory created by the conical body, which differs from that of traditional mills. The fall vector of the ball in a TCM is perpendicular to the conical body. The balls do not fall vertically downwards, but at a slight angle against the movement of the material along the mill, i.e., in the direction of the material feed. Under the influence of gravity, a ball with a large diameter (large weight) falls further and a small one closer, thus sorting the grinding media by size.

In addition, during a joint flight movement, a ball with a large diameter pushes a ball with a small diameter towards the discharge side. The process of the free flight of balls and their ideal classification is clearly visible in transparent TCM models.

The different trajectories of falling balls along the length of the conical body and the classification of the balls have a decisive influence on the grinding process. Traditionally, this primary task is solved by a labor-intensive and ineffective selection of the armor lining profile. However, the lining wears out quickly and the expected effect diminishes significantly.

Furthermore, the corresponding trajectory movements of the balls are not performed in every cross-section of the mill, but rather follow a trajectory over the entire length of the chamber. In TCM, the trajectories of falling balls depend strictly on the radius of the conical body and are not critically decisive for the lining profile. The lining in TCM serves to protect the mill body and increase the coefficient of friction of the loads of the balls when lifting to separation and transition to free flight.

We have developed a design for armor plates that can be installed in each belt of a conical housing by alternating only three standard sizes, reducing their total number by 20%. A rolled lining has also been developed for the conical shell.

In the TCM, instead of six technological hatches on the hull, which are intended for repair work and additional loading (reloading) of balls, one or two are sufficient, which simplifies the design, increases the strength of the hull, and reduces dust and maintenance. The conical body allows you to significantly reduce and simplify the routine loading and reloading of the ball filling.

Global experience [2] in loading balls (Table 1) recommends a gradual reduction of balls in chambers with a constant value of ∆ɸ = 3%. In the single-chamber TCM, this idea is implemented automatically, and the upper level of the balls is aligned on the same horizontal line along the entire length of the cone.

This makes it possible to simplify the labor-intensive and time-consuming process of reloading a decommissioned mill by organizing continuous automatic reloading over time, simply by throwing a ball with a maximum diameter into the chute of a running mill at an interval calculated from the degree of wear of the balls per 1 ton of crushed material. As the ball wears down, it moves along the cone and the next new ball takes its place. The additional feeding of balls to the CGM is regulated every 9 days (the regulations are usually not adhered to due to the labor intensity of the work and the downtime of the mill), but due to the abrasion of the entire ball group, productivity decreases by 13.7% [3].

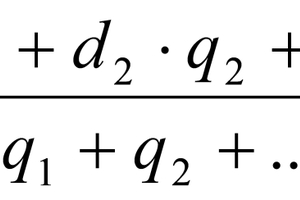

The most important unresolved issue is the choice of ball assortment, which is generally related to the weighted average ball diameter dcp.

⇥(1)

Formula for weighted average ball diameter where: q – weight of the ball with the corresponding diameter contained in the grinding load, i.e.; d – ball diameter, mm.

The assortment of grinding media should allow for a rational grinding load, which makes it possible to create a large contact area with the material, prevent the free passage of material in the spaces between the balls without grinding, and at the same time ensure the passage of the crushed fractions in the mill. In TCM, this problem is solved by the automatic self-regulation of the weighted average ball, regardless of the originally selected ball selection.

The different types of grinding (Table 1) along the chamber length of classic ball mills lead to uneven abrasion of the grinding media. The phenomenon is particularly evident in mining rod mills. The treated rods, which are single grinding bodies that are rigid along their length, are ground into a cone, i.e., the abrasion rate at the end of the mill is higher than at the beginning. The conical housing, which ensures optimal technological operating conditions for the balls, makes it possible to compensate for the uneven abrasion of the grinding media over the entire length of the mill and reduce the overall wear of the balls by 20%.

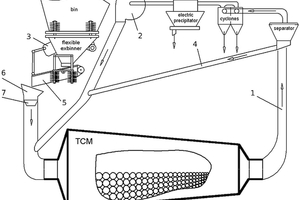

4 Closed circuit for grinding cement based

on TCM

With TCM, you can completely eliminate the disadvantages of the classic grinding scheme by implementing the simplest closed circuit of the ventilated coal grinding type in a TKM drum ball mill (Formula 1) using a mill fan with a capacity of 20% of the TCM capacity.

The grinding scheme is radically simplified. This increases the utilization of the TCM‘s working time, as the number of additional devices, which, with the exception of the mill fan, are static devices, is significantly reduced.

Accordingly, capital costs, space requirements, and operating costs are significantly reduced.

ShBM flow separators classify the material and ensure that the remaining coal dust is within the required limits (6 to 7% on the R90 screen).

A centrifugal separator can be used for better classification. Compared to an open grinding cycle, the proposed scheme adds a separator and a mill blower, but eliminates bulky pneumatic chamber pumps, a compressed air line with compressor, and suction blower.

This makes the proposed closed-circuit scheme even simpler than the open-circuit grinding scheme, and the TCM is much simpler and more efficient than a classic ball mill.

The TCM has a cone nozzle (confusor) that improves the aerodynamics of the closed grinding cycle and prevents “steaming” of the material in the mill. In addition, a closed, ventilated air flow instead of an aspirated air flow lowers the temperature of the mill and the ground material.

In addition to the radical simplification of the classic closed-circuit auxiliary equipment scheme, the TCM eliminates the outlet grid and air lift along with the intermediate chamber partitions. This increases the working volume of the TCM by 11.5%, which further increases the productivity and working time utilization of the unit. The overall economic effect consists not only in the introduction of the closed grinding cycle, but also in the efficiency of the TCM itself.

5 Summary

The universal TCM is designed for operation in open or closed cycles for grinding various dry or wet materials in the raw material processing phase.

The TCM is a radical improvement in the new generation of grinding units, making it possible to rationalize the functioning of the balls in a very simple, complete, and optimal way in accordance with modern grinding theory and practice.

The originality and fundamental novelty of the proposed technical solutions are confirmed and protected by numerous patents.